Bread consumption dates back thousands of years, making it one of the world’s oldest and most widespread staple foods. Although bread is often associated with taste, pleasure and tradition, its perception as a vector of nutrition and health remains complex

Is there solid, consistent scientific evidence linking bread consumption as a category to the risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease? Let’s take a look at these questions in this first chapter on bread and health.

Researchers at the Lesaffre Institute of Science & Technology conducted an extensive review of the scientific literature to understand the relationship between bread and various aspects of health. Nearly 200 studies including epidemiological, observational and clinical trials conducted since 2000 were rigorously reviewed. The results of this critical analysis were then validated by an independent Reading Committee and published in the journal Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition.

Let’s start with a common misconception still held by many diets.

-

No, bread doesn’t make you fat

Observational studies(2) fail to establish a link between habitual bread consumption (defined as 4 to 5 slices a day in the EU) and the risk of overweight and obesity. It is in fact the total calories, the composition of our diet and our level of physical activity that determine weight gain or loss, and not the specific consumption of bread, whether white or wholemeal.

Observational studies showing a link with overweight and obesity have focused on diets containing bread, but also fast food, sweet drinks, sweets and desserts.

Common question: should bread be excluded from a low-calorie diet? A study(3) conducted over 16 weeks showed no difference in weight loss between the low-calorie diet group with bread and the one without. On the positive side, the bread group was more compliant with the diet. The same study showed an advantage in terms of satiety for bread-containing meals over bread-free meals.

In conclusion, bread eaten sensibly is not associated with overweight, obesity or increased abdominal fat(4).

-

No, bread is not empty calories

Both accessible and with a particularly interesting nutritional content, bread is a staple food in many households around the world. In fact, bread makes a positive contribution to nutrient intakes thanks to its major contributions of dietary fiber, vegetable protein and important micronutrients

Did you know that bread meets the European “source of protein” criteria because it contains at least 12% energy from protein? And that white bread is a “source of fiber” (3g or more per 100g), while wholemeal bread is “high in fiber” (6g or more/100g), again according to European criteria(5).

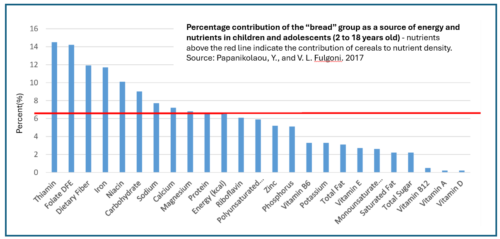

For children and teenagers, bread (along with cereals) a particularly good source of energy. As shown in figure(6) below, it also contributes to the nutritional density of several nutrients, including thiamine, folic acid, dietary fiber, iron and sodium.

Bread plays a key role in providing nutrients to vulnerable populations, often thanks to flour fortification in certain developing countries.

-

No, we can’t say that bread is bad for blood sugar levels and should be excluded from the diet.

Although white bread has a high glycemic index, there is no strong evidence that the inclusion of white bread in the diet is associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes. Controlled clinical trials are needed to establish a causal relationship.

What we can say, however, is that in the starchy foods category, it’s advisable to favor wholemeal breads, pasta and rice, and legumes for their fiber and protein content. These complex carbohydrate-based foods have a more favorable impact on blood sugar levels than refined products.

Did you know that consuming half a serving of dark bread a day or more, as part of a balanced diet, is associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes compared with no dark bread consumption(7)?

Wholemeal and seeded breads are indeed more beneficial than refined wheat bread for regulating blood sugar levels in the short term and eating wholemeal breads may have a protective effect against type 2 diabetes, although this needs to be confirmed by long-term clinical trials.

Controlling your bread intake doesn’t mean excluding it altogether but rather consuming a quantity in line with current recommendations, and favoring varieties that are richer in fiber. Bread is an integral part of a balanced diet.

-

No, eating bread every day is not dangerous for your cardiovascular health.

Observational studies to date show no association between bread consumption in general (of all types) and the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Clinical trials on the impact of bread (of all types) on cardiovascular risk factors such as blood lipids, hypertension, etc. are currently lacking. No studies have been found, for example, on white bread and hypertension, but one study assessed the relationship between refined cereal consumption and hypertension and reported no significant correlation.

But what can we say in terms of prevention?

Well-designed clinical trials have shown that oat, barley and rye bread improve blood lipids and markers of endothelial function compared to white bread.

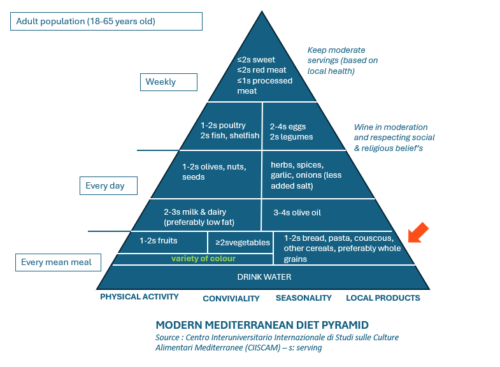

It’s also worth remembering that bread consumption is an integral part of a so-called “Mediterranean” diet, recommended for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Bread, generally unrefined, accounts for 30 to 40% of energy(8).

Note that bread contains components such as resistant starch, soluble fiber (e.g. oat and barley bread) and healthy oils (e.g. seed bread) that are known to improve cardiovascular risk factors.

Current question: Is the amount of salt in bread a risk?

Depending on the type of bread and the country, salt content varies between 0.09 g/100g and 2.65 g/100g of bread. In some countries, such as France, Turkey and the United States, bread is a major contributor of salt(9). It should be remembered that the World Health Organization recommends less than 5g/day/adult; salt in large quantities and over the long term in fact favours the onset of cardiovascular disease and, more particularly, high blood pressure.

This is why, in some countries where bread consumption is very high, a low-salt bread could help reduce the risk of hypertension, although further clinical trials are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Are you curious?

To appreciate the scope of this analytical work, we invite you to discover the full narrative review entitled “Nutritional intake and the relationship with health of bread consumption”.

As you can see, there are still major gaps in scientific knowledge about bread and health. A key point in understanding the evidence on bread consumption and health is that bread is rarely consumed on its own and therefore needs to be studied for its impact in the context of the overall diet, not in isolation. For this reason, further research is needed to assess bread consumption or omission, and to determine whether its substitution by other staple foods may have an impact on health. Such research may include large-scale clinical trials and dietary modeling studies.

See you soon for a new chapter dedicated to preconceived ideas contradicted by science.

Notes :

(1) Ribet L, Kassis A, Jacquier E, Monnet C, Durand-Dubief M, Bosco N. The nutritional contribution and relationship with health of bread consumption: a narrative review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024 Nov 18:1-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2024.2428593 ; https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10408398.2024.2428593#d1e222

(2) Observational study: A study in which the researcher does not intervene in the natural course of events, but simply observes a phenomenon or a population. References to observational and clinical studies can be found in (1).

(3) Gonzalez-Anton, C., R. Artacho, MD Ruiz-Lopez, A. Gil and MD Mesa. 2017. Modification of appetite by bread consumption: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 57 (14): 3035-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2015.1084490; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26479182(open in new window).

(4) Loria-Kohen, V., C. Gómez-Candela, C. Fernández-Fernández, A. Pérez-Torres, J. García-Puig and LM Bermejo. 2012. Evaluation of the usefulness of a low-calorie diet with or without bread in the treatment of overweight/obesity. Clinical Nutrition 31 (4): 455-61. Evaluation of the usefulness of a low-calorie diet with or without bread in the treatment of overweight/obesity – Clinical Nutrition; https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0261561411002330

(4) CIQUAL nutritional database (ANSES) – Bread (Average food)

(5) Papanikolaou, Y., and V. L. Fulgoni. 2017b. Grain foods are contributors of nutrient density for American adults and help close nutrient recommendation gaps: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009-2012. Nutrients 9 (8):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9080873org/10.3390/nu9080873; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28805734/

(6) Hu Y, Ding M, Sampson L, Willett WC, Manson JE, Wang M, Rosner B, Hu FB, Sun Q. Intake of whole grain foods and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three prospective cohort studies. BMJ.370:m2206. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2206 ; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32641435/

(7) D’Alessandro A, De Pergola G. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a proposal for Italian people. Nutrients. 2014 Oct 16;6(10):4302-16. doi: 10.3390/nu6104302. PMID: 25325250; PMCID: PMC4210917. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25325250/

(8) World Action on Salt and Health , based at Queen Mary University of London and Şule Aktaç, Aybike Cebeci, Yeşim Öztekin, Mustafa Yaman, Mehmet Ağırbaşlı, Fatma Esra Güneş, Differences in the salt amount of the bread sold in different regions of Turkey: A descriptive study, Human Nutrition & Metabolism, Volume 33,2023,200211,ISSN 2666-1497,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hnm.2023.200211.