From end-of-year celebrations, weddings, christenings and birthdays to sports victories, there is always a special occasion to pop a bottle of bubbly. But what makes this sparkling wine so exceptional? Part of the answer has to do with microscopic living organisms: champagne yeasts. Classified as fungi, these microorganisms are what gives this famous sparkling drink many of its unique characteristics.

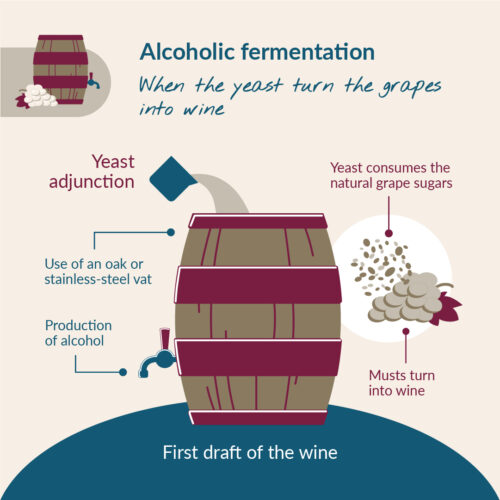

Primary fermentation

Like in every alcoholic beverage, the role of yeasts is first to produce alcohol. For champagne, and all wines for that matter, yeasts feed on the sugar of grape must—which is the liquid obtained from the pressing of grapes—to produce alcohol. But unlike many oenological yeast strains that give wines their rich and complex aromas, champagne yeasts are fairly neutral-tasting to preserve the natural taste of wine and capture the qualities of its terroir. The wine resulting from primary fermentation is high in acidity and light in flavour, and very different from the prestigious sparkling wine we know as champagne.

Secondary fermentation (forming of bubbles)

Secondary fermentation is where most of the magic happens, where the transformation from a still wine into an exquisite champagne takes place. The wine is then bottled with a mixture of yeasts and sugar. The yeasts feed on the sugar to produce alcohol and turn it into carbon dioxide. The so-called CO2 is trapped in the sealed bottle, dissolves into the wine and forms bubbles. Secondary fermentation, also known as prise de mousse (forming of bubbles), has to be a slow and steady process to give the champagne its fine bubbles.

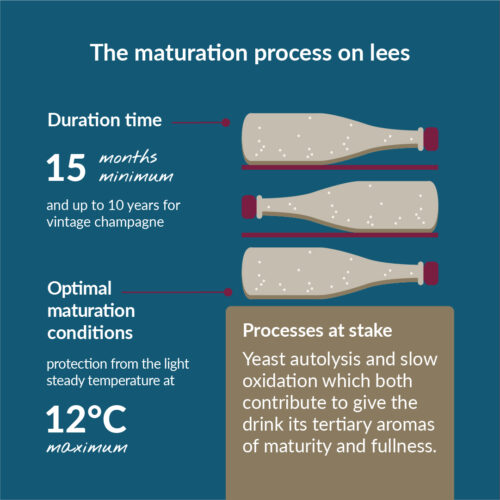

Maturation on lees

By the end of secondary fermentation, the champagne yeasts die and form a sediment at the bottom of the bottle known as “lees”. But dying yeast cells continue to interact with the wine, as they release a number of molecules to make it rounder. Maturation on lees is a process that takes place in the well-known cool and dark cellars of champagne houses. Maturation lasts for a minimum of 15 months for a non-vintage champagne and 36 months for a vintage, and several years for more prestigious blends.

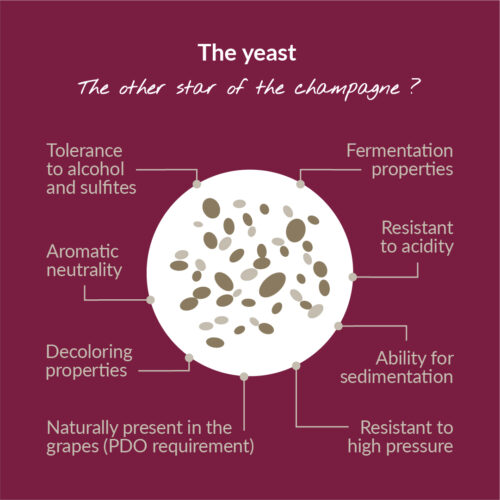

High-tolerance yeast

Yeast cells play an essential role throughout the champagne production process, which is why for the last centuries champagne winegrowers have striven to select them with the utmost care. Champagne yeasts have to be tolerant enough to adapt to the stressful environmental conditions to which they are exposed, especially grape must acidity and pressure that builds up in bottles during secondary fermentation. They also have to be alcohol- and sulphite-tolerant. Despite exposure to a relatively low temperature, champagne yeasts are expected to ferment properly before the autolysis process takes place, where yeast cells start degrading to release compounds that contribute to bubble and foam stability and impart aromas.

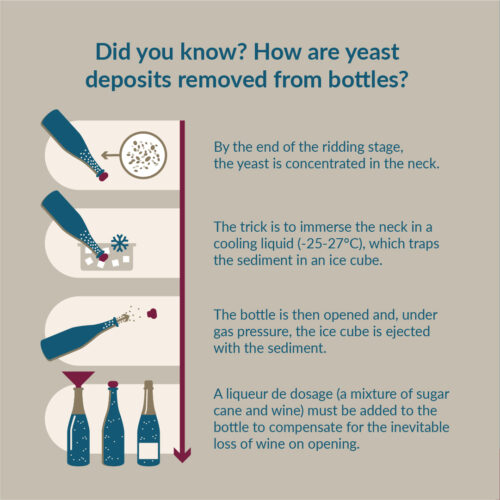

Their ability to sediment is just as important. Good sedimentation will make the disgorgement process easier, which means getting the yeast sediment out of champagne bottles after maturation. Furthermore, champagne is a blended wine made from several grape varieties, including Chardonnay but also the two black grapes Pinot noir and Pinot Meunier. Champagne yeasts can absorb colour pigments to give this ultimate prestigious sparkling wine its crystal-clear colour (except for rosé champagne).

Bacteria also have a role to play

Other types of microorganisms can also be used to make champagne. Œnococcus œni bacteria, for instance, transform the tarter malic acid found in wine into softer-tasting lactic acid. This process, known as malolactic fermentation, takes place before secondary fermentation to reduce acidity levels and ensure microbial stability while imparting notes of brioche and butter to the wine.

Focus on Saccharomyces cerevisiae galactose

Not every type of yeast can meet all these criteria. Only the Saccharomyces cerevisiae species, in particular the S. bayanus strain, can accomplish such feats. These species of yeast are naturally found in grapes—a requirement of the Champagne controlled designation of origin (Appellation d’Origine controlée, AOC)—and help winegrowers to enhance the aroma profile of a wine from a terroir not well suited for wine production. However, the selection and use of a yeast strain is no easy task. This is where Fermentis by Lesaffre’s expertise is invaluable, either to support the winemakers who want to cultivate their own strain or to offer ready-to-use yeast like SafŒno™ VR 44 (comes also in an organic version). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae galactose active dry yeast is the result of more than 25 years of expertise and is an Easy 2 Use product designed to make the life of winemakers easier. The yeast strain can be directly inoculated into the must to start the alcoholic fermentation process, or previously rehydrated ahead of secondary fermentation. Drawing on this simple, safe and repeatable process which also lowers the risk of contamination and gives champagne wines a crisp, fresh and clean profile, Fermentis by Lesaffre becomes a valuable partner for champagne winegrowers.