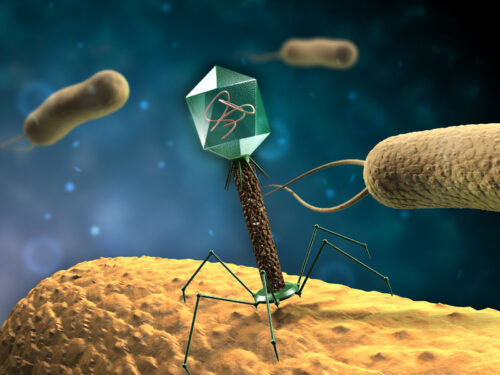

Discovered in the 1920s but rapidly outshined by antibiotics and forgotten, bacteriophages are returning to centre stage as promising antimicrobial compounds with potential applications in numerous sectors, including the agro-food industry. These naturally occurring viruses are predators of bacteria, harmless to humans and animals. They have a strong natural specificity, making them valuable candidates for both the precise detection and control of pathogens at every stage of the food production process.

From broad spectrum to targeted solutions

Historically, the agriculture and processing sectors have heavily relied on the use of antibiotics. As industries move away from these products, whose imprudent use and overuse gave rise to drug resistant bacteria, phages and their derivatives are increasingly being recognised as viable complimentary approaches to keep food risk-free.

“Generally, the food industry takes a multi hurdle approach to food safety,” explains Joelle Woolston, VP for Laboratory Operations at Intralytix, an American company specializing in bacteriophages for the environment, food and health sectors, and a Lesaffre partner for the past 6 years. “Any and all types of bacteria, from farm-to-fork, are knocked down using different methods such as heat, chemicals or antibiotics. It’s a broad-spectrum approach. Phages, on the other hand, are much more specific. Each type of phage targets one specific kind of bacteria.”

For a long time, the specificity of phage approaches was seen as a drawback for biocontrol purposes. All bacteria were bad bacteria; and broad acting agents were good at eliminating all bacteria. There was no need for a finer blade. However, in light of recent understanding of microbiome systems and interactions, it has come to researchers’ attention that wiping out all germs can have unexpected consequences. It leaves a clean slate, an empty gap left to be conquered by any bacteria, good and bad alike.

“Pathogenic bacteria can reclaim that space, and come back stronger than before. It is better to leave the competitive nature of bacteria to guide the balance of the microflora,” adds Woolston. Correctly selected phages will exterminate only one type of pathogenic bacteria, leaving the beneficial ones untouched. As the space clears, their numbers expand, preventing pathogen recurrences and further securing the zone. “We’re taking something that’s already present in the food and just putting the right ones in the right spot at the right time, at a slightly higher concentration. Phages don’t seem to shift the balance of the microbiome”. Most studies have shown that phage use leaves the bioflora quite intact. They tend to die off once their host, the bacteria, has been consumed because there’s nothing to support their growth.

Precise bacterial control throughout the processing line

Using phages does entail knowing which initial bacteria are problematic before they can be targeted and eliminated. Their use isn’t universal. However, this isn’t problematic for the food industry. The troublesome pathogens, such as E. coli, Salmonella, and Listeria, are quite well recognized and characterized. To be effective, phages need to come into contact with the bacteria and latch onto them. The correct concentration of phages must also be used, as phages tend to be more effective in a more liquid environment. Luckily, a lot of foods have a high amount of water or use water at some stage of their processing.

“Phages are pretty easy and straightforward to use, very environmentally friendly, and safe for employees to use. They can be used anywhere bacteria are a problem and there seems to be no adverse effects from their ingestion,” according to Woolston. Today, the meat industry in particular has taken on phages in their processing lines. “They can be applied at any point, it really depends on the final product. To knock down salmonella, for example, one might apply phages pre-harvest, such as on the eggs or the chicks right after they hatch or in the chicken’s drinking water or food. More commonly, phages are applied post-harvest, directly onto the foods in the food processing line. We have studied different facilities to investigate how their processing system works and tailor checkpoints where phages are the most effective.”

In general, phages are not used alone. They are added in as an extra step of the processing line, or can substitute a sterilizing method that one might want to replace such as radiation, which isn’t very environmentally friendly or safe to use, and affects flavour. The goal is to create many hurdles for the bacteria to go through before making it to the final product. “However, phages can be susceptible to many of the same things bacteria are, which means it is important to time phage introduction. One can’t add bleach right after phages and expect results,” specifies Woolston.

Adapting to a moving field

In 2006, Intralytix was the first company to obtain FDA (US Food & Drug Administration) approval for the use of phages for food safety. After jumping through hoops, showcasing why they are safe to use in foods, how their manufacturing process make them safe, and how their use is safe, the company convinced the regulatory body phage use has real potential for the food industry. “It was an interesting regulatory process because phages don’t really fit into a category,” describes Woolston. “Regardless of which regulatory agency we’ve gone to, they’ve never really seen this before. Both sides have been trying to figure it out and are working together to get through the regulatory process. We’re constantly learning from the FDA, the FDA’s constantly learning from us. Unfortunately, the European Union has yet to approve phages for use in food.”

One regulatory consideration is the use of only lytic phages in preparations. Lytic phages don’t integrate into the bacterial genome and therefore do not lead to the spread of bacterial DNA. In her own words: “It helps prevent concerns regarding shifts in bacterial population that you don’t intend. It is important to limit your impact on the existing microbiome. The regulatory hurdles are stringent about this point.”

Another regulatory consideration is the development of resistance. Woolston suggests pre-empting bacterial evolution by using lytic phage cocktails “Bacteria are surprisingly adept and agile at defying phages,” details Woolston. “Just like when faced with antibiotics, they constantly evolve and develop resistance. However, phages are constantly evolving along side the bacteria whereas there really hasn’t been a new antibiotic discovered in over half a century. As the bacteria change, one can generally find new phages that can effectively attack them.”

She adds: “Today, we have the ability to add phages to our cocktails without resubmitting for FDA approval, as long as they meet the initial criteria. The industry is constantly evolving, and with it the problematic bacteria. We are capable of shifting and adapting our phage cocktail to fit these changes and target the industry’s needs.”

While food processing facilities lend themselves quite easily to phage application, phages could be applied wherever there are bacteria. “I could see their application expand into a couple different markets like raw petfood, aquaculture or plant production. For each sector, we will need to adapt to the industry – and their specific pathogens – to create customized phage cocktails. Hopefully, in the future, phages will be seen as the safeguards of food safety that they are. It is important to move past the concept that they are viruses, and understand that not all microbes are bad. Phages could be the probiotics of the food industry, if we let them.”

Bacteriophage ready to inject its genetic material into host bacteria